WINNIPEG -- Federal polar bear research near Churchill has been put on hold for the first time since 1980 because of restrictions on travel due to the global coronavirus pandemic.

Nick Lunn, an Alberta research scientist with Environment and Climate Change Canada, travels to northern Manitoba every year in September to conduct polar bear monitoring programs.

Lunn's work involves sedating more than 100 bears so measurements and other biological samples can be taken.

The long-term data set that has been cultivated over the past 40 years is the best in the world for this species, he says. But this year that unbroken stream of information will be fractured.

“Long-term data sets can handle a missed year in the time series more easily than short-term data sets,” he said in an email from Edmonton.

“Techniques in analysis have advanced so much over the past 30 to 40 years that there are now ways to deal with gaps for certain types of questions. So while (it's) disappointing to miss fall 2020, it won't be the end of the world for the long-term nature and value of the program.”

That said, it doesn't mean the missed data is inconsequential. “Without knowing what was missed, it is not possible to assess the significance,” he said.

For example, one of the first strong signals that polar bear health was linked to climate change came from a single year of data in 1992. That year the bears weighed significantly more than usual, and researchers were able to link that event with the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines.

The eruption launched so much particulate matter into the atmosphere that it blocked sunlight, temporarily cooling the Arctic in the spring of 1992. As a result, among other things, there was a later breakup of the sea ice in western Hudson Bay that year - and consequently better-fed, fatter polar bears.

If there had been no data collection in 1992, this specific event and link might have been missed, Lunn said.

As researchers look to better understand the effects of climate change on these animals, they are expanding their understanding of what influences the bears' health.

“We know that (sea ice) breakup was later this year than last, so we would have expected bears to be in better condition this year, which hopefully translates into (more and bigger) cubs in the spring. Unfortunately, we won't know how much better condition they may have been in,” Lunn said.

During the summer when travel restrictions to northern Manitoba were lifted, many researchers, including Lunn, were hopeful they'd be able to get to northern communities.

However, this fall the northern travel ban was reinstated. While provincial health officials allowed an exemption to the travel ban for research and tourism, many universities and government institutions have opted for more stringent restrictions internally. Thus, Lunn and his colleagues at Environment and Climate Change Canada have been grounded.

On Thursday, more stringent public health orders were implemented for the northern region and Churchill, however there was no mention of ending the Churchill travel exemption.

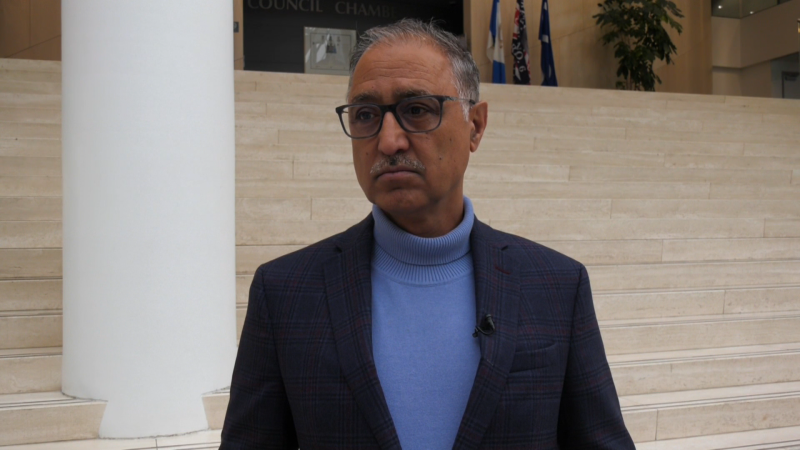

Andrew Derocher, professor of biological sciences at the University of Alberta, has worked with the polar bear population near Churchill on and off since the early 1980s. He says the impact of the missing research is significant.

“Losing the monitoring conducted by Environment and Climate Change Canada this year was a huge loss to polar bear science and to Arctic monitoring on a global scale. The western Hudson Bay population is the baseline study from which we have learned about how climate change affects polar bears,” he said.

“Other polar bear populations have far less data and far less insight into the mechanisms of change brought by warming.”

Derocher's research is among the work being affected this year, as he is also unable to travel to northern Manitoba. Much of his research is conducted in concert with federal researchers.