An Edmonton man who has been living with a brain injury for years is speaking out, saying he’s frustrated with the lack of mental illness support he’s receiving.

Life can be a constant struggle for Kirk Sweitzer.

Sweitzer was at work when a crate dropped on his head eight years ago.

Since then he’s been living with a brain injury, which has led to mental illnesses like depression and anxiety.

But Sweitzer says the most frustrating part is the lack of support and mental health programming available to him.

“I have no services right now,” Sweitzer tells CTV News.

Sweitzer had been receiving help from the Canadian Mental Health Association’s Community Rehabilitation Outreach Program (CROP).

The program was funded by Alberta Health Services, but two years ago, funding stopped and now Sweitzer says he’s not getting the support he once was.

“I’m not contributing the way I used to,” he said.

“I have a fear I’m going to live on the streets eventually because I don’t have anybody watching out for me.”

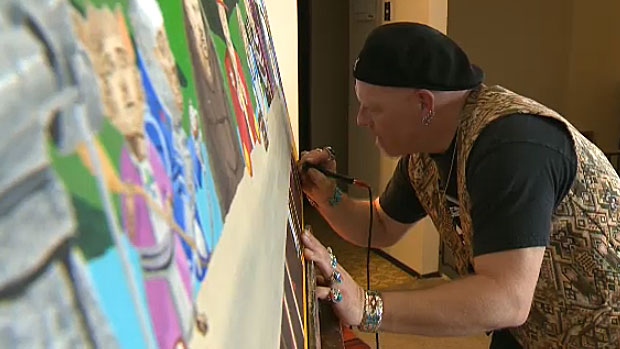

Sweitzer is now an artist.

He paints about current events and tries to share political views through his work.

He says the brain injury robbed him of the ability to properly read and write so instead – he paints.

Sweitzer says for the longest time, he hid the reason why he chose to share political opinions through paintings because of how people reacted.

“There is so much stigma with brain injury,” Sweitzer said. “I’ve been not telling people that I have this injury because they will walk away.”

For years, Sweitzer had worked with a mental health outreach worker through CROP, who he says helped him with his taxes, got him to art shows and even booked him occasional speaking positions - where he could share his story with local psychology students.

Since funding for the program was discontinued by AHS, Sweitzer says he’s no longer out in the community as much as he’d like to be.

“I live in this house, that’s it,” Sweitzer said. “I have all these built-up ideas and I’ve got nowhere to put them. I want to contribute.”

Mental health funding dollars used in a different way

Alberta Health Services says the decision to reallocate funding for mental health services was not an easy one.

Mark Snaterse, the executive director of addiction and mental health, says the province is constantly evaluating ways to spend mental health dollars.

“Every once in awhile we need to change, we need to adapt, we need to evolve because the needs of our clients change and evolve,” Snaterse said.

“We had decided to discontinue funding that program so we could take the dollars and provide other programs that our clients and families and the public were telling us were needed.”

Reports from 2008-2011 state how effective CROP was – with one suggesting 92 per cent client satisfaction.

But AHS believed services provided by CROP could be accessed in other ways.

“We were confident that it wasn’t the only way of delivering the service and that the clients would be able to transition to some type of alternate service,” Snaterse said.

"The most important tool in mental health is hope"

Sweitzer says he isn’t able to drive, lives with anxiety, and calls himself one of Alberta’s most vulnerable.

He says when CROP was discontinued, he received no transition help.

“At any time, was anything set up to put people in to different programs, and that’s the truth,” Sweitzer said. “There was no overlap in service. There was zero.”

Sweitzer adds the current services he receives is not as good as what he had through CROP.

Snaterse says he will personally meet with anyone who feels their needs aren’t being met – including Sweitzer.

“If there is someone who, two years down the road, is saying they have needs that aren’t being met then certainly we’ll re-engage with them and get them connected,” he said.

It’s estimated there are more than 6,000 Canadians who become permanently disabled after a traumatic brain injury each year.

Research suggests 49 per cent of patients suffer a psychiatric illness in the first year after injury.

Sweitzer hopes he can get help he knows he needs, and adds that hope is the most important thing he – and anyone dealing with mental illness – can have.

“The most important tool in mental health is hope,” Sweitzer said.

“Hope is everything. Hope that you can get better, hope that you have a better life, a better future.”

Sweitzer wants to publish a book detailing how brain injury has affected his life.

He believes the story might help others living with the condition - and help health care professionals.

With files from Carmen Leibel