Immersive VR therapy considered helpful to vets with PTSD in Alberta study

What's called 3MDR (or Motion-Assisted, Multi-Modal Memory Desensitization and Reconsolidation) is a virtual reality PTSD treatment that aims to help military personnel heal from their combat-related trauma. In 3MDR therapy, the patient is fully immersed in the experience using virtual reality. They walk on a treadmill toward a triggering image, wear VR goggles, and can even choose the images they see and the music they listen to. (Courtesy: Heroes in Mind, Advocacy and Research Consortium (HiMARC) at the University of Alberta)

What's called 3MDR (or Motion-Assisted, Multi-Modal Memory Desensitization and Reconsolidation) is a virtual reality PTSD treatment that aims to help military personnel heal from their combat-related trauma. In 3MDR therapy, the patient is fully immersed in the experience using virtual reality. They walk on a treadmill toward a triggering image, wear VR goggles, and can even choose the images they see and the music they listen to. (Courtesy: Heroes in Mind, Advocacy and Research Consortium (HiMARC) at the University of Alberta)

An immersive therapy using virtual reality to treat patients with PTSD is proving to be a promising treatment for Canadian veterans.

What's called 3MDR (or Motion-Assisted, Multi-Modal Memory Desensitization and Reconsolidation) is a virtual reality PTSD treatment that aims to help military personnel heal from their combat-related trauma.

It was created by Col. Eric Vermetten, an officer and psychiatrist with the Dutch Armed Forces who teaches psychiatry at the University of Leiden.

Vermetten developed 3MDR therapy in the Netherlands, and came to Edmonton in 2019 to help launch the Canadian study alongside Dr. Suzette Brémault-Philips, director of Heroes in Mind, Advocacy and Research Consortium (HiMARC) at the University of Alberta.

In traditional therapy, both the therapist and patient are seated and techniques and interventions are offered to the patient.

In 3MDR therapy, the patient is fully immersed in the experience using virtual reality. They walk on a treadmill, wear VR goggles, and can even choose the images they see and the music they listen to.

"They're walking or moving forward as they are doing the therapy… the therapy is they're walking towards pictures that they have self-selected of their index trauma," said Vermetten.

"It could be a child that's blown up, or it could be another combat scene or it could be something that stands out for them during their deployment, which is a completely different way of delivering treatment."

He says it's highly personalized because the therapist and patient together choose a total of seven photos that reminds the patient of their trauma, and they work through each distressing image gradually over a series of sessions.

The patient looks at each image for three to five minutes, and over time they increase their tolerance to look at the images that are the most traumatic.

The entire time the therapist is beside them, supporting and empowering the patient to work through their trauma, says Vermetten.

"The moving forward really gives you the internal attribution, like, 'I did it, it's not you [who] did it for me, I did it,'" said Vermetten.

The therapy also uses two pieces of music chosen by the patient, one that reminds them of the time period during which the trauma occurred and one from a more current time.

Vermetten says the older song is a "warm up" before the patient is exposed to the distressing pictures, and the second piece of music is played at the end of the session to remind them of a contemporary moment.

"That's why it's multi-modal. It's visual, it's olfactory sometimes, it's acoustic and it's motion-based."

The therapy also uses eye movement to engage the patients. An oscillating ball is projected on the screen with a number that changes every time the ball reaches a corner of the screen.

"So that dual task processing, thinking back to the trauma, being engaged, and at the same time disengaging by doing a working task assignment is one of the contributing factors to reconsolidation and towards the working mechanism to the intervention," said Vermetten.

Sessions are 45 minutes to an hour, and patients do six sessions using the 3MDR therapy technique.

Brémault-Philips says that 3MDR is one of the tools that patients can utilize if they are feeling stuck, or like they aren’t making any progress with their traditional therapy methods.

"An individual might be receiving a course of various kinds of interventions and then receive a course of six sessions of 3MDR and then return to their therapy," said Brémault-Philips.

POSITIVE OUTCOMES

Treatment isn't always easy, but Brémault-Philips says study participants quickly see the benefits the therapy provides.

"They learn to regulate in a different way than what I've seen in other forms of therapy particularly for those who haven't had success with other forms of therapy."

She says the treatment's impact on families is one of the other major positive outcomes.

"Members can be the people they want to be again, have something of their life back, have meaning and purpose back, relationships can improve. Families can stabilize."

Vermetten says he thinks that positive internal attribution by the patient contributes to the long-lasting therapeutic change seen in the participants.

FINDING THERAPY THAT WORKS

In the 2019 Life After Service study, 24 per cent of Canadian veterans reported symptoms of PTSD. After traditional treatment, two thirds of veterans retained their diagnosis of PTSD.

"Some of those in the military and veteran population and other populations can also experience what we call moral injury, so, complex PTSD," said Brémault-Philips. "It makes it sometimes more difficult for people to have success."

The dropout rate of therapy is higher among military members than the civilian population, often because they're avoiding things that trigger their trauma, says Vermetten.

"They wait a long time before they seek help, so it's five years, 10 years down the line," said Vermetten.

"What they struggle with is trying to survive, and they do survive by cognitively avoiding going to places, thinking about it, and that can last only so long."

He says eventually when something significant happens in their life, the death of a spouse or a divorce for example, often the symptoms of PTSD can no longer be avoided and "the whole thing explodes."

Vermetten says the longer a person with PTSD waits to ask for help, the harder it can be for professionals to treat, and for them to work through.

FUTURE PLANS

Forty-five CAF members were selected to take part in the two-year study that started in 2019, which has had some setbacks due to the pandemic. The program is currently paused until case numbers are lower. Those behind it are expecting to resume early in 2022.

With funding from donors, the Royal Canadian Legion, the Government of Alberta, and Department of National Defense, they're hoping to bring the technology to more clinics in Edmonton and Calgary.

Eventually they hope to offer 3MDR treatment to public safety personnel and health-care workers to deal with the trauma they may have experienced during the pandemic.

Vermetten and the team is also considering whether 3MDR can be offered sooner to those diagnosed with PTSD.

"The veterans like it, and what's encouraging for us and for me also is the dropout is so low," said Vermetten.

Veterans interested in participating in future 3MDR treatment can contact Brémault-Philips at HiMARC.ca.

With files from CTV News Edmonton's Kyra Markov

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Demonstrators kicked out of Ontario legislature for disruption after failed keffiyeh vote

A group of demonstrators were kicked out of the legislature after a second NDP motion calling for unanimous consent to reverse a ban on the keffiyeh failed to pass.

RCMP uncovers alleged plot by 2 Montreal men to illegally sell drones, equipment to Libya

The RCMP says it has uncovered a plot by two men in Montreal to sell Chinese drones and military equipment to Libya illegally.

Tom Mulcair: Park littered with trash after 'pilot project' is perfect symbol of Trudeau governance

Former NDP leader Tom Mulcair says that what's happening now in a trash-littered federal park in Quebec is a perfect metaphor for how the Trudeau government runs things.

Government agrees to US$138.7M settlement over FBI's botching of Larry Nassar assault allegations

The U.S. Justice Department announced a US$138.7 million settlement Tuesday with more than 100 people who accused the FBI of grossly mishandling allegations of sexual assault against Larry Nassar in 2015 and 2016, a critical time gap that allowed the sports doctor to continue to prey on victims before his arrest.

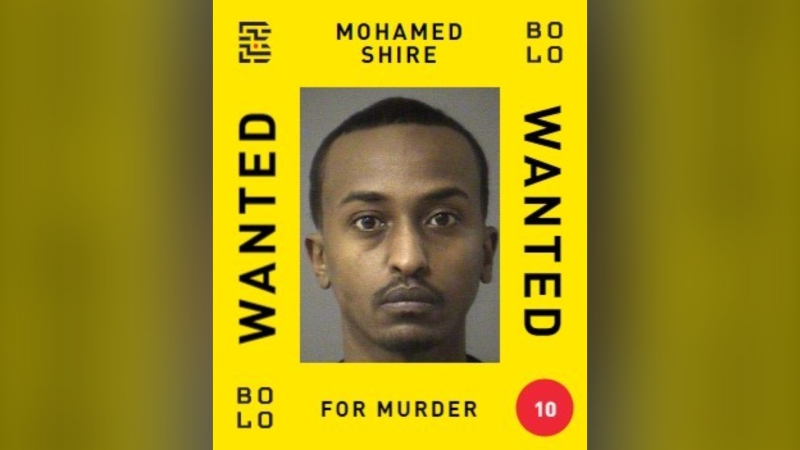

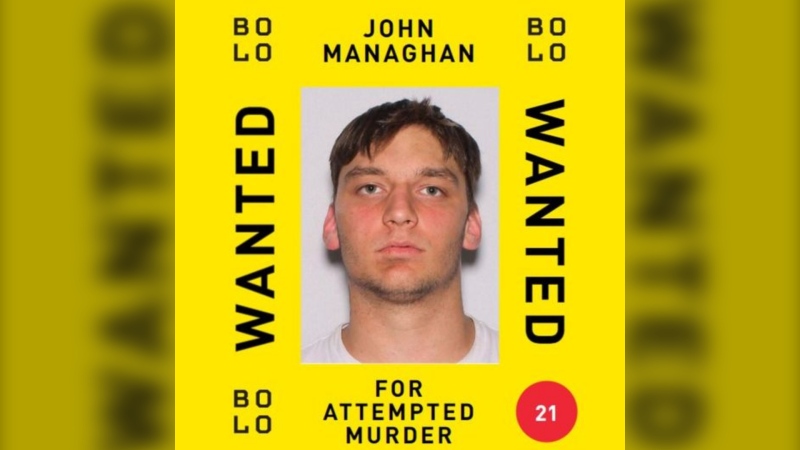

Man wanted in connection with deadly shooting in Toronto tops list of most wanted fugitives in Canada

A 35-year-old man wanted in connection with the murder of Toronto resident 29-year-old Sharmar Powell-Flowers nine months ago has topped the list of the BOLO program’s 25 most wanted fugitives across Canada, police announced Tuesday.

Doctors ask Liberal government to reconsider capital gains tax change

The Canadian Medical Association is asking the federal government to reconsider its proposed changes to capital gains taxation, arguing it will affect doctors' retirement savings.

Pro-Palestinian protests roiling U.S. colleges escalate with arrests, new encampments and closures

The student protests of Israel's war with Hamas that have been creating friction at U.S. universities escalated Tuesday as new encampments sprouted and some colleges encouraged students to stay home and learn online, after dozens of arrests across the country.

Tabloid publisher says he pledged to be Trump campaign's 'eyes and ears' during 2016 race

A veteran tabloid publisher testified Tuesday that he pledged to be Donald Trump 's 'eyes and ears' during his 2016 presidential campaign, recounting how he promised the then-candidate that he would help suppress stories that had the potential to harm the Republican's election bid.

Keeping these exotic pets is 'cruel' and 'dangerous,' Canadian animal advocates say

Canadian pet owners are finding companionship beyond dogs and cats. Tigers, alligators, scorpions and tarantulas are among some of the exotic pets they are keeping in private homes, which pose risks to public safety and animal welfare, advocates say.