EDMONTON -- The police chief says Edmonton Police Service has spent the months since the summer’s protests against police brutality and systemic racism reflecting on its goals and impact, and concluded change will take a concerted effort by police, social agencies and governments.

“We held a mirror up to ourselves, our policies, our actions,” Chief Dale McFee opened his remarks to Edmonton city council on Monday.

"The way we're set up directly impedes our ability to effectively address the growing needs of our vulnerable population. This is because there's a lack of coordination and cooperation between service providers and funders. We should be working in teams with shared priorities and aligned performance metrics.”

In July, council asked for data on the number of police calls driven by social or public health factors that could be responded to by interagency partnerships, as well as analysis on system gaps which drive crime and service demand.

McFee and the Edmonton Police Commission came back Monday to advocate for better integration of social services – like mental health and addictions care – into police response.

He said the change would reduce the number of vulnerable people that enter the criminal judicial system – and instead see them connected to supports – thereby reducing demand on police and allowing more dollars to be reallocated to other community initiatives.

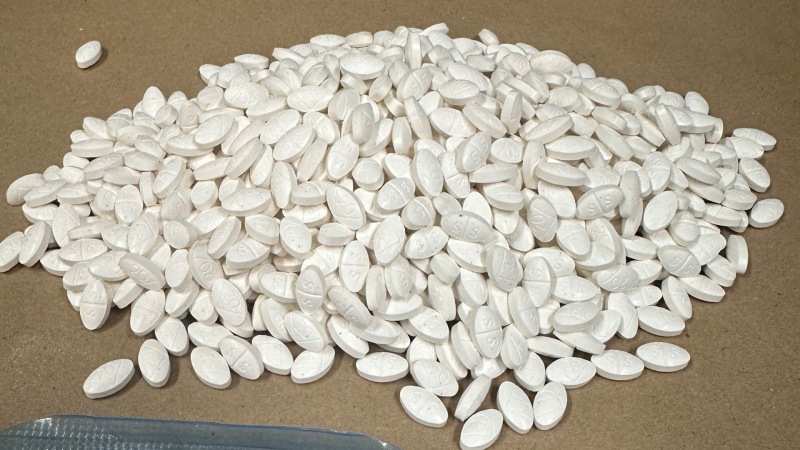

He explained the city’s officers respond to mainly two groups: serious reoccurring offenders who are responsible for the majority of violence in the city, and marginalized and at-risk communities who’ve become “unnecessarily entrenched in the arrest, remand, release cycle.”

The report to city council estimated 30 per cent of what police do is social work.

In 2019, Edmonton officers were dispatched some 192,500 times ending in roughly 38,400 arrests of 18,300 people.

According to EPS, 10,600 individuals were only arrested a single time. A third, about 6,200 people, were arrested between two and five times. The top one per cent of people – 217 individuals – accounted for 4,490 or 10 per cent of arrests. One person was arrested 70 times.

Between 2000 and 2017, the chief said 233 people have together accounted for 19,000 calls.

“There’s a system breakdown here,” he said. “Something’s not working in that system.”

As well, police helped other agencies, like EMS or firefighters, in nearly 4,800 calls in 2019. The 24/7 crisis diversion team was also involved in 22,528 calls that year.

Out of 48,800 calls that were initially classified as social disorder, about 22,000 were later reclassified as something else after officers responded.

The question at the centre of the demand issue, said EPS’ executive director of information management and intelligence, is how the service is supposed to identify which 911 calls don’t need officer response.

"The challenge is how, with only the initial complainant information, to disentangle those 38,113 calls for service that required no further EPS involvement from the 24,321 occurrences that do?" Sean Tout asked.

McFee told councillors the solution isn’t more money.

“The whole system is designed around supply: We just need more of this, we just need more of this, we just need more of this. And that’s not sustainable,” he commented.

“What we need to do is take some of the people that are in that vulnerable state out of the system on the front end.”

‘WE’RE IN THE MIDDLE OF THE SANDWICH RIGHT NOW’

The report was received favourably by the councillors, with Mayor Don Iveson even saying EPS seemed “committed to innovation and different forms of partnership.”

And for Ward 6 Coun. Scott Mckeen, the data presented Monday had been missing from the June and July conversations on defunding police.

“It was very one sided, so we’re getting the other side of the story today.”

Other councillors, however, questioned whose responsibility it was to take the first step towards change, given police and social services funding comes from multiple sources.

“The province… it seems like they really should be the ones leading this alignment,” commented Ward 10’s Michael Walters.

McFee said EPS was leading the charge “because we’re in the middle of the sandwich right now.”

“We’re leading because right now we take the calls.”

But, he noted, any systemic improvement would require partnership from the city, province and social agencies, through which funds and resources are “siloed.”

“It’s not to point fingers,” the chief said. “We can continue to do this and move money around, we’ll just have the same problem we’ve had for the last several years.”

McFee pointed to a 2019 dedication by EPS of $28 million to a community safety and wellbeing bureau, intended to change the way police handle calls involving mental health and social disorder, as evidence his police service has already started the work.

As well, over the summer, city council decided – with McFee’s support – to reallocate $11 million in inflation adjustments to the police budget over 2021-22 to housing, social and community services, as well as a community safety and well-being task force.

The police commission will deliver another report to council on Dec. 7 on how to take a balanced approach to community safety.

With files from CTV News Edmonton’s Jeremy Thompson