Schools in Afghanistan built by Central Alberta non-profit closed after Taliban takeover

A central Alberta non-profit that opened multiple schools in Afghanistan has had its schools shut down after the Taliban takeover.

It was in late 2001, when the Taliban were overthrown in Afghanistan, five years after they seized the capital of Kabul and the country.

In those five years, the Taliban imposed strict rules based on its interpretation of sharia law. Specifically, their interpretation significantly limited the freedoms of women and young girls.

Most women were not allowed to work or go to school, and many of them were forced into marriage at a young age.

Twenty years later, the Taliban has taken control of Afghanistan again, and those advocating for open education for the children of Afghanistan are fearful of what the future holds.

One of those advocates is Eric Rajah. He is the co-founder of A Better World Canada: a non-profit organization located in Lacombe that has invested over $35-million in numerous projects across the world focused on providing education, healthcare, and clean water.

Rajah still remembers visiting Afghanistan for the first time in 2004 and seeing the lack of schooling infrastructure.

“The schools that we visited, most of them, were in tents. Torn out tents,” Rajah said.

“Their future was, of course, marred because the Taliban were in control, but the moment the Taliban were ousted, everybody wanted a school. It was a perfect fit.”

In 2010, A Better World Canada started the 100 Classroom Project, which, over the years, has opened 12 schools, providing education to over 18,000 students—many of them young girls.

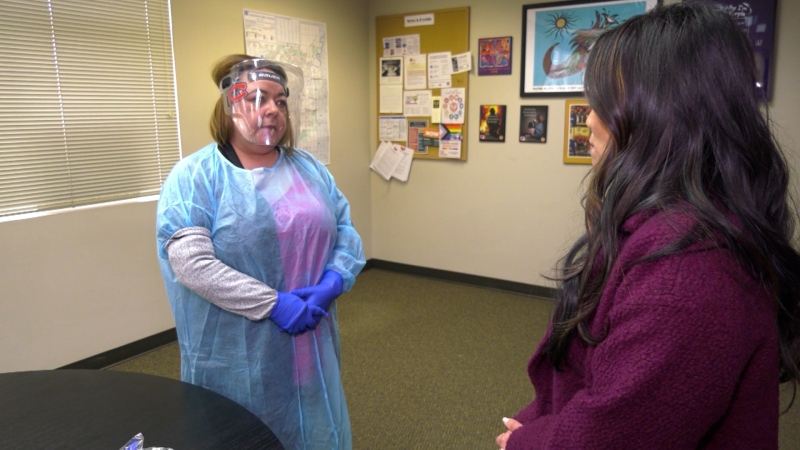

Girls in a classroom in Afghanistan. (Supplied/A Better World Canada)

Girls in a classroom in Afghanistan. (Supplied/A Better World Canada)

Girls in a classroom in Afghanistan. (Supplied/A Better World Canada)

“The thirst for learning in Afghanistan is huge among young people, especially among the girls,” Rajah said. “I’ve had conversations with these girls who want to become lawyers, who want to be leaders in their country. It’s absolutely amazing.

All of the schools are in the northern Afghanistan province of Jowzjan, which is known for being an anti-Taliban stronghold.

“We were convinced that this was an area that was referred to as ‘Free from the Taliban.’ This province particularly did not want the Taliban there,” he said.

“We felt that this was a safe place to get the girls and young people back in school.”

However, two weeks ago, the Taliban seized the province’s capital Sheberghan, effectively taking control of the province. As a result, the schools have been shut down.

“Right now, the schools are closed for the safety of the students,” he said. “They’re afraid. They don’t want to send their children out of the house.”

Rajah said he is discouraged, but he is holding on to a sliver of hope. He pointed to the Taliban’s claim that this is a different Taliban than the one that ruled in the late 1990s.

A Taliban spokesman said the group would respect women’s rights “within the framework of Islam Law”, and they would allow women and girls to keep attending school.

“The Taliban have said, ‘We are a new version, and we need the country to grow, and we don’t want it to go backwards,’ so we are hanging on that hope, so to speak.”

However, Javid Noori, the project manager for the 100 Classrooms Project, is skeptical. He lives in Afghanistan’s capital Kabul with his family.

He believes the Taliban in control now is the same Taliban of 20 years ago.

“They have not changed,” Noori said. “I see their behaviour with the people after 21 years, they are the same people.”

Noori pointed to the protest in Jalalabad where, reportedly, at least three people were killed and several wounded, by the Taliban, after protesters attempted to erect Afghanistan’s national flag.

“It was a protest only because of the national flag,” said Noori. “The Taliban wanted to replace the flag and the people said, ‘This is the national flag, you have to form your government and then after that you can remove the national flag.’

“Because of that small thing, they killed people. They have not changed.”

UNICEF estimates that 3.7 million Afghan children are out-of-school, and 60 per cent of them are girls. Furthermore, out of all the schools in Afghanistan, only 16 per cent are all-girls schools.

Noori said he expects the conditions to worsen under the Taliban.

“We have experience of Taliban in Afghanistan before 2001 in 1999. There was no university, they were chasing young girls for forced marriage,” he said.

“They just show that they are going to let the girls go to school, but I’m sure if the Taliban are there, and there’s no proper negotiation with them, there not going to let the girls go to school.”

Noori said he has considered leaving the country, but the recent chaos at the Kabul airport has discouraged him. If he cannot leave, he is desperate to get his 11 year-old-daughter out of the country.

“If I am not able to move out of this country, definitely I’m going to move her out from here,” Noori said.

“I don’t want her to live under this kind of regime where she is not allowed to attend the school, do her education, and also facing forced marriage.”

But, his desperation does not cloud the gratitude he feels for the people who helped him build the schools in Afghanistan.

“I just want to thank you Canadians and the international community for helping the children of Afghanistan. For helping my children,” he said. “The communities are there, the schools will be there, the buildings will be kept safe. We will not let the Taliban use the schools as army bases.

“I’m sure in the future, the children will use those classrooms, which are built by your money, by your donations. Thank you very much for all the donations you made for Afghanistan.”

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

DEVELOPING Man sets self on fire outside New York court where Trump trial underway

A man set himself on fire on Friday outside the New York courthouse where Donald Trump's historic hush-money trial was taking place as jury selection wrapped up, but officials said he did not appear to have been targeting Trump.

BREAKING Sask. father found guilty of withholding daughter to prevent her from getting COVID-19 vaccine

Michael Gordon Jackson, a Saskatchewan man accused of abducting his daughter to prevent her from getting a COVID-19 vaccine, has been found guilty for contravention of a custody order.

She set out to find a husband in a year. Then she matched with a guy on a dating app on the other side of the world

Scottish comedian Samantha Hannah was working on a comedy show about finding a husband when Toby Hunter came into her life. What happened next surprised them both.

Mandisa, Grammy award-winning 'American Idol' alum, dead at 47

Soulful gospel artist Mandisa, a Grammy-winning singer who got her start as a contestant on 'American Idol' in 2006, has died, according to a statement on her verified social media. She was 47.

'It could be catastrophic': Woman says natural supplement contained hidden painkiller drug

A Manitoba woman thought she found a miracle natural supplement, but said a hidden ingredient wreaked havoc on her health.

Young people 'tortured' if stolen vehicle operations fail, Montreal police tell MPs

One day after a Montreal police officer fired gunshots at a suspect in a stolen vehicle, senior officers were telling parliamentarians that organized crime groups are recruiting people as young as 15 in the city to steal cars so that they can be shipped overseas.

The Body Shop Canada explores sale as demand outpaces inventory: court filing

The Body Shop Canada is exploring a sale as it struggles to get its hands on enough inventory to keep up with "robust" sales after announcing it would file for creditor protection and close 33 stores.

Vicious attack on a dog ends with charges for northern Ont. suspect

Police in Sault Ste. Marie charged a 22-year-old man with animal cruelty following an attack on a dog Thursday morning.

On federal budget, Macklem says 'fiscal track has not changed significantly'

Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem says Canada's fiscal position has 'not changed significantly' following the release of the federal government's budget.