Since it's unknown which virus will become the next pandemic, these U of A scientists are preparing for a number of possibilities

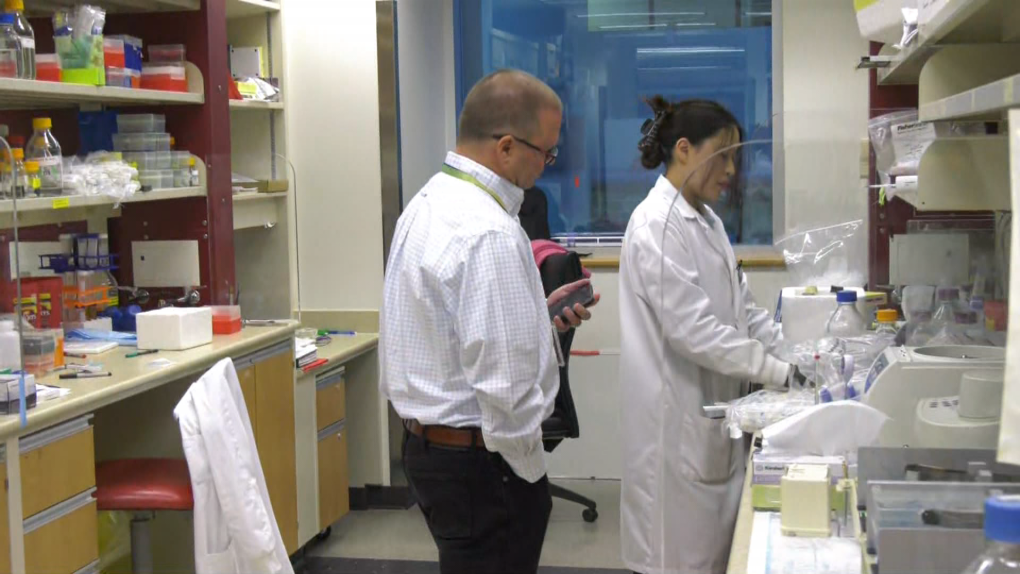

Matthias Götte, a virologist and chair of the University of Alberta's medical microbiology and immunology department, left, is leading a team of about 15 people in Edmonton working on how to better prepare the world for the next pandemic, including Hery Lee, a third-year PhD student.

Matthias Götte, a virologist and chair of the University of Alberta's medical microbiology and immunology department, left, is leading a team of about 15 people in Edmonton working on how to better prepare the world for the next pandemic, including Hery Lee, a third-year PhD student.

When it comes to the numerous viruses that have the potential to spur the world's next pandemic, there's not a one-size-fits-all approach to planning medical treatment. But a one-size-fits-several solution may do the trick, a University of Alberta scientist says.

Matthias Götte, a virologist and chair of the U of A's medical microbiology and immunology department, is leading a team of about 15 people in Edmonton working on how to better prepare the world for the next pandemic.

"COVID-19 taught us a lot of lessons and we have to get better. We have to be better prepared; we have to respond quicker," he told CTV News Edmonton in a recent interview.

His idea is to have a drug template, of sorts, for each of the kinds of viruses that could lead to a pandemic.

Götte's team studies virus families that have "high" pandemic potential and the drugs that most effectively target each.

"As soon as a pandemic hits or an outbreak hits, you would like to have on-hand therapies or medical counter measures that work immediately," Götte said.

"When a new virus emerges that belongs to one of these families of viruses we're working on, we have a good starting point and can tailor to the new pathogen. That's the idea."

Götte and his team specifically study viral polymerase enzymes – a.k.a., the engine of the virus which drives it to replicate and spread.

According to Hery Lee, a third-year PhD student working under Götte, one of the questions they try to answer is: "After the virus has been targeted with a specific antiviral, how does the virus then respond?"

"Is it going to develop what we term as resistance?" she said. "So is the virus going to take from its arsenal something that can counteract the antivirals that we work with?"

The method has been successful in work treating chronic viral disease, like HIV and Hepatitis C, Götte noted.

"Now, we are trying to develop antiviral drugs by targeting the engine of the virus to other viruses, like Ebola."

Ebola belongs to the filovirus family, as does Marburg, which can cause severe hemorrhagic fever. Other virus families the U of A team is targeting include picornaviruses, which cause the common cold, and flaviviruses, the cause of yellow fever and dengue fever.

In a globalized world, more pandemics are likely, Götte believes.

But during previous outbreaks – such as of HIV, Hepatitis C, Ebola, and Zika – scientists "missed opportunities" to prepare in the same way he is working to now, the U of A professor says.

"There was a lot of funding in the beginning and then the virus disappeared and the funding disappeared, before we were actually able to cross the finish line. That should not happen again."

The U of A researchers are collaborating with colleagues in California and North Carolina under a program funded by the National Institutes of Health in the United States. The new Antiviral Drug Discovery (AViDD) Centers for Pathogens of Pandemic Concern, of which Götte's work is a part, are backed by nearly $600 million.

With files from CTV News Edmonton's Nahreman Issa

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Mark Carney reaches out to dozens of Liberal MPs ahead of potential leadership campaign

Mark Carney, the former Bank of Canada and Bank of England governor, is actively considering running in a potential Liberal party leadership race should Justin Trudeau resign, sources tell CTV News.

'I gave them a call, they didn't pick up': Canadian furniture store appears to have gone out of business

Canadian furniture company Wazo Furniture, which has locations in Toronto and Montreal, appears to have gone out of business. CTV News Toronto has been hearing from customers who were shocked to find out after paying in advance for orders over the past few months.

WATCH Woman critically injured in explosive Ottawa crash caught on camera

Dashcam footage sent to CTV News shows a vehicle travelling at a high rate of speed in the wrong direction before striking and damaging a hydro pole.

A year after his son overdosed, a Montreal father feels more prevention work is needed

New data shows opioid-related deaths and hospitalizations are down in Canada, but provincial data paints a different picture. In Quebec, drug related deaths jumped 30 per cent in the first half of 2024, according to the public health institute (INSPQ).

Rideau Canal Skateway opening 'looking very positive'

As the first cold snap of 2025 settles in across Ottawa, there is optimism that the Rideau Canal Skateway will be able to open soon.

Much of Canada is under a weather alert this weekend: here's what to know

From snow, to high winds, to extreme cold, much of Canada is under a severe weather alert this weekend. Here's what to expect in your region.

Jimmy Carter's funeral begins by tracing 100 years from rural Georgia to the world stage

Jimmy Carter 's extended public farewell began Saturday in Georgia, with the 39th U.S. president’s flag-draped casket tracing his long arc from the Depression-era South and family farming business to the pinnacle of American political power and decades as a global humanitarian.

'A really powerful day': Commemorating National Ribbon Skirt Day in Winnipeg

Dozens donned colourful fabrics and patterns Saturday in honour of the third-annual National Ribbon Skirt Day celebrated across the country.

Jeff Baena, writer, director and husband of Aubrey Plaza, dead at 47

Jeff Baena, a writer and director whose credits include 'Life After Beth' and 'The Little Hours,' has died, according to the Los Angeles County Medical Examiner.