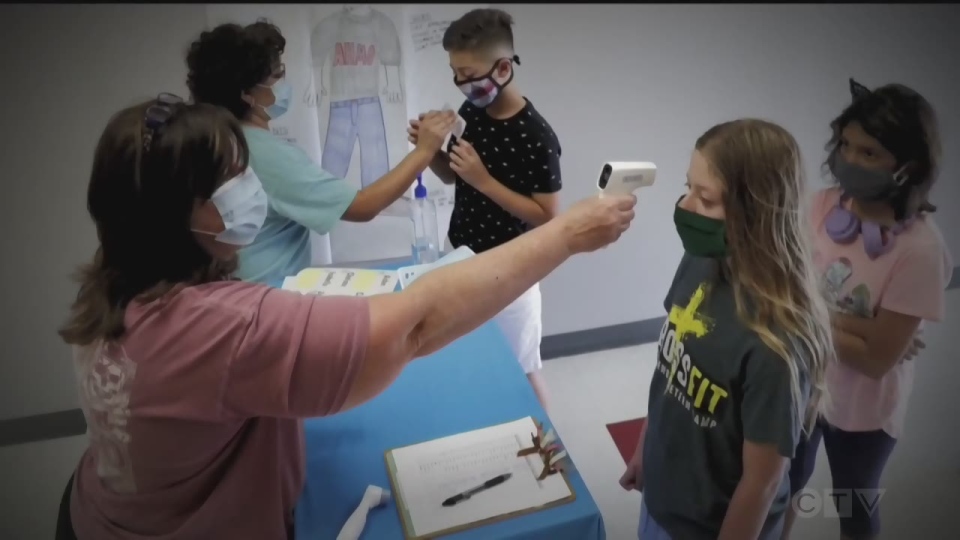

EDMONTON -- As Alberta navigates the third wave of COVID-19, health experts are concerned of the high transmission rates of the disease in children, and in particular the long-term impacts it could have on their development months after diagnosis.

According to pediatrician, Dr. Tehseen Ladha, Albertans under 18 make up close to a third of the province’s COVID-19 cases.

Out of the provinces more than 23,000 active cases, more than 6,000 are under the age of 20 and 2,500 are under the age of nine.

“These are completely healthy children,” Ladha said.

“And some of these completely healthy children are ending up in the hospital, and some are ending up in the ICU, and then there’s this whole other group that may have had the mildest of COVID-19 infections that then end up developing more severe long term symptoms that are really debilitating.”

Stephen Freedman, professor of pediatrics and emergency medicine at the University of Alberta, added: “The more children that are infected, the more children that are exposed to it, the more children we will see that are seeking hospital care, require hospitalization and potentially have complications of the illness.”

Ashley Itz, an employee with CTV News Edmonton, says her family caught COVID-19 last November.

Ashley and her husband Kyle have two young sons: Emmett, 6, and Austin, 4.

“The oldest brought it home from school, from a close contact and then we all got it,” Kyle said.

Even after recovering from COVID-19, Kyle said Austin still complains about the same leg cramps he had while infected with the disease.

“You don’t know how it’s going to affect you, it affects everyone differently,” Ashley added.

Healthcare professional are seeing more COVID-19 induced pneumonia in teenagers, Ladha said, whereas in younger children, the symptoms can be more severe. This can include inflammation of the organs like the kidneys, brain and heart, and in some cases, seizures.

Some of the more common symptoms include headaches, abdominal pain, muscle aches, fatigue, nausea and difficulty concentrating.

“Vaccines aren’t our ticket out of this,” Ladha said. “And for children they won’t be vaccinated for quite some time.”

According to Ladha, with the new variants factored into the surge of recent outbreaks in the province, if a child brings home COVID-19 from school or from anywhere it’s almost 100 per cent likely they will infect their parents or whoever else lives with them.

“We’ve gotten to a space where it’s simply too dangerous to be keeping children in schools where they’re at such high risk and bringing their families high risk,” she added.

While hospitalization of children is rare, COVID-19 in schools is becoming more common.

“There are currently active alerts or outbreaks in 808 schools, which represents 33 per cent of schools in the province,” Chief Medical officer of Health Dr. Deena Hinshaw said on Monday.

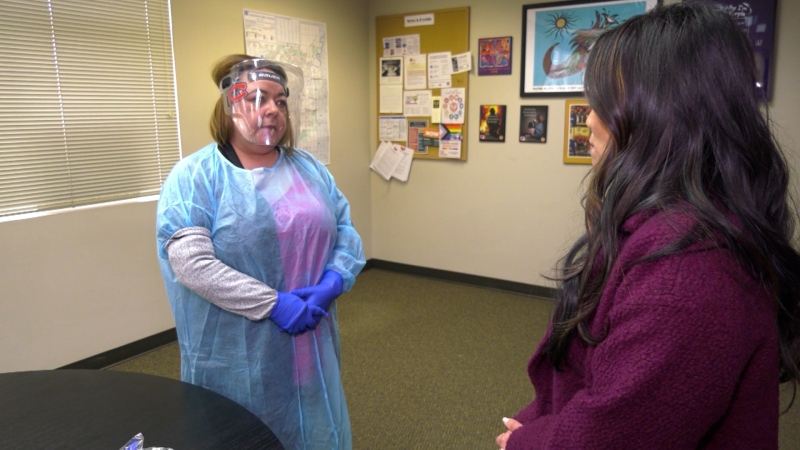

The other area of concern for Ladha is how COVID-19 is disproportionately impacting marginalized children.

“So kids who are racialized, Indigenous communities children living in poverty, refugees and intergenerational households those are the children who have parents who may be essential workers that may have to take public transport that are higher risk of exposure that don’t necessarily have paid sick leave,” she told CTV News.

While the healthcare system is becoming overwhelmed, Ladha said it’s trickling down into the pediatric care ward as well. Pediatric care specialists are being redeployed to other care units and pediatric kids are having to share rooms, which she says is unusual.

“Many chronically ill children, such as those with cancer, are trying to be treated at home because they’re so scared of being exposed to COVID-19 in the hospital,” Ladha said.

“The aim is to decrease community transmission.”

With files from CTV Edmonton’s Touria Izri