It's possible that kids got TB, died from milk served at Alta. residential school: experts

GRAPHIC WARNING: This article contains details readers may find disturbing.

A historian and a health studies professor agree that bovine tuberculosis from untested animals may have been one of the things that killed residential school children in eastern Alberta.

On Tuesday, investigators with the Acimowin Opaspiw Society (AOS) held a press conference in the Saddle Lake Cree Nation to discuss a preliminary report into the deaths of kids at the Blue Quills Residential School.

Executive director Leah Redcrow said her group has evidence of several mass graves in the area, which she believes contain students of Blue Quills and an earlier version of the institution called Sacred Heart Residential School.

One of the graves was accidentally discovered by crews digging new burial sites in 2004, Redcrow said.

"The mass grave was filled with children-sized skeletons wrapped in white cloth. And we now know that the white cloth they were wrapped in were bed sheets from the residential school," she told reporters.

Redcrow believes the milk was deadly because she said students were assessed by doctors before attending the schools.

"They were healthy, there were no issues with them. Suddenly a month later they were infected with tuberculosis," she said.

Records show students drank milk from on-site cattle several times a day. The same documents suggest there was no pasteurization equipment and the cows were not regularly tested for tuberculosis, Redcrow said.

"These children died in the hundreds from drinking unpasteurized, raw cow’s milk," she said.

Leah Redcrow, executive director of Acimowin Opaspiw Society, speaks to reporters in Saddle Lake, Alta., on January 24, 2023. (Jay Rosove/CTV National News)

Leah Redcrow, executive director of Acimowin Opaspiw Society, speaks to reporters in Saddle Lake, Alta., on January 24, 2023. (Jay Rosove/CTV National News)

'TUBERCULOSIS RAN RAMPANT'

Experts say more investigating needs to be done but it is possible that the society's findings are correct. And if true, they reveal a glaring hole in the health policies of Canada's residential schools.

"We know that tuberculosis ran rampant in those schools. Not least, because of the poor nutrition that was available," said historian Catherine Carstairs from the University of Guelph.

"Certainly, it's possible that they could have gotten tuberculosis from drinking unpasteurized milk. It's also very likely that the milk was unpasteurized."

The school operated at two sites, one in Saddle Lake and more recently one closer to the town of Saint Paul, from 1989 to 1990.

"We had veterinary recognizance for bovine TB probably by 1910. The thing is residential schools weren't part of the commercial dairy economy so they didn't have the same kind of veterinary recognizance keeping an eye on their cattle," said James Daschuck, a professor of kinesiology and health studies at the University of Regina.

"So what that means is unpasteurized milk was provided to those kids probably for decades after non-indigenous kids were protected by pasteurization."

Daschuk also wrote a book called Clearing The Plains: Disease, Politics Of Starvation, And The Loss Of Indigenous Life and is currently researching the impact of introduced species like horses and domestic cattle on the well-being of First Nations people.

"The rest of us, we were protected by pasteurization. And all it is is boiling it. Why didn't they boil it? But again, this is a sign of just how low a priority the health of those children was," Daschuk said.

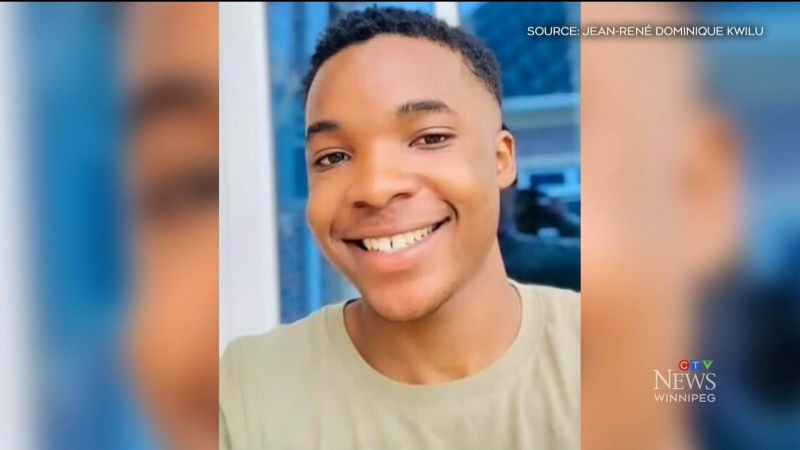

Residential school survivor and researcher Eric Large in Saddle Lake Cree Nation on January 24, 2023. (Jay Rosove/CTV National News)

Residential school survivor and researcher Eric Large in Saddle Lake Cree Nation on January 24, 2023. (Jay Rosove/CTV National News)

'VIOLENCE, ILLNESS, STARVATION, ABUSE AND DEATH'

The preliminary report by the Acimowin Opaspiw Society also alleges that a staff member killed children by pushing them down the stairs and then threatened witnesses to be quiet.

"The investigation has received disclosures from intergenerational survivors, whose parents witnessed homicides at the Saint Paul site," it states.

The report says the man accused in those deaths died in 1968.

Eric Large, a residential school survivor and researcher with AOS, said he found documents for 215 students who died between the ages of 6-11, but whose remains are still unaccounted for.

"The amount of missing children is extensive...The institution was strife with violence, illness, starvation, abuse and death," Large said when the investigation was launched last year.

AOS is now asking other First Nations looking into unmarked graves and mass deaths to check for records on the milk that students drank at their local schools.

"Most residential schools had a school farm. They had cattle and that cattle was purchased by the Department of Indian Affairs," Redcrow said.

"A lot of what this is, is getting spiritual justice for our family members who are missing. I myself didn't know that my grandfather had 10 siblings die in this school."

She said AOS is now looking for a coroner to sign off on excavating at the site. The report states the society plans to repatriate the remains after DNA matches them to surviving relatives.

If you are a former residential school student in distress, or have been affected by the residential school system and need help, you can contact the 24-hour Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419, or the Indian Residential School Survivors Society toll-free line at 1-800-721-0066.

Additional mental-health support and resources for Indigenous people are available here.

With files from CTV News Edmonton's Alison MacKinnon and CTV National News' Bill Fortier

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Parts of Canada could see the Northern Lights on New Year's Eve. Here's where you could see

While fireworks have become a popular way to celebrate the arrival of the new year, many Canadians could be treated to a much larger light display across the night sky.

Ottawa family returns home after chaotic Costa Rica trip

After spending almost 48 hours longer than intended in Costa Rica, the Sachs family has finally returned home.

'Dangerous person alert' ended as police locate dead suspect in Calgary double murder

The suspect in a double homicide that took place in Calgary on Sunday night has been discovered dead by police.

More than US$12M worth of jewelry and Hermes bags stolen from U.K. home

Police are searching for a burglar who stole more than £10 million ($12.5 million) worth of bespoke jewelry in north-west London in what is thought to be one of the biggest thefts from a British home.

Border agents seize $2M worth of cocaine bound for Canada at Coutts

Authorities at the Coutts, Alta., border crossing seized 189 kilograms of cocaine, with an estimated value of about $2 million, that was being shipped into Canada.

Matthew Gaudreau's widow welcomes their first child months after his death

Four months after his death, the widow of Matthew Gaudreau announced the birth of their first child. Gaudreau, 29, and his NHL star brother Johnny Gaudreau, 31, were killed after being struck by a driver in August.

'McDonald's wouldn't open': Here are B.C.'s 10 worst 911 nuisance calls of the year

What do overripe avocados, stinky cologne and misplaced phones have in common? Generally speaking, none of them warrant a call to 911.

Man who peed on B.C. RCMP detachment injured during arrest, watchdog says

A police watchdog is asking witnesses to come forward after a man who allegedly peed on a B.C. RCMP detachment "sustained an injury" during his arrest.

opinion Tom Mulcair: Grading Trudeau's performance in 2024, and what's ahead for him in the new year

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is about to enter the final year of his mandate and, quite possibly, of his political career, writes Tom Mulcair in his column for CTVNews.ca. The former NDP leader takes a snapshot of Trudeau's leadership balance sheet as a way of understanding how he got to where he is in the polls.