EDMONTON -- Alberta is reporting 904 opioid-related deaths in the first 10 months of 2020, a sobering record surpassing the province's current death count of COVID-19.

Premier Jason Kenney says the novel coronavirus has had an impact on those opioid numbers, initially reducing access to in-person treatment programs along with reports some people used federal COVID-19 income supports to purchase drugs.

“It's important for us to learn from these factors that may have driven a significant increase in overdose deaths earlier this year,” Kenney said at a virtual news conference Friday.

But he noted the province has also invested $140 million over four years for mental health and addictions programs, including $40 million for opioid addictions.

Alberta's opioid death rate originally peaked at 806 in 2018 before falling to 627 last year.

The 904 opioid deaths this year are calculated up to the end of October. There have been 815 deaths so far this year linked to COVID-19.

The Opposition NDP said Kenney's United Conservative government has contributed to the rise in deaths by cutting front-line aid, including closing a safe consumption site in Lethbridge earlier this year.

“We have seen throughout the COVID-19 pandemic that Jason Kenney puts his personal ideology ahead of professional public health advice,” said Heather Sweet, the NDP's critic for mental health and addictions.

“He has taken the same approach to the toxic overdose crisis, and it's led to unnecessary deaths.”

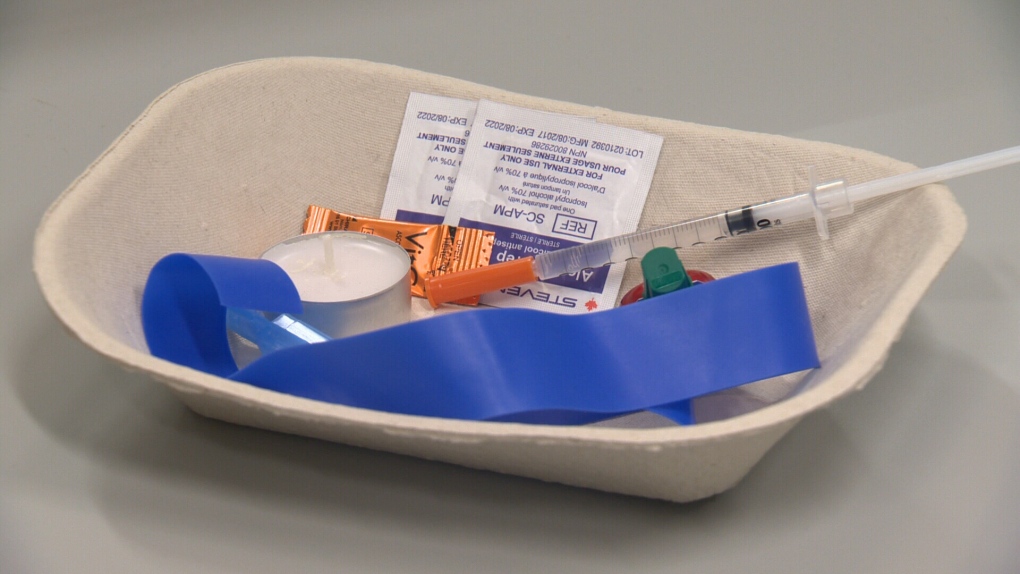

Safe consumption sites allow addicts to use drugs in a supervised setting. Advocates say it's a way to expose addicts to treatment while stopping them from dying of overdoses. Critics, including Kenney's government, argue it's enabling an addiction and that the best course of action is to focus on treatment and recovery.

Kenney said the ARCHES site in Lethbridge was closed because an audit found financial irregularities. He added that a mobile site has replaced it and opioid-related deaths in Lethbridge are decreasing.

Elaine Hyshka, an assistant professor at the University of Alberta's School of Public Health, said the province needs to take specific action to address the crisis, starting with safe drug supply programs.

When the pandemic started, she said, border closures disrupted traditional illicit drug supply routes. The resulting vacuum was filled by “new actors” distributing even more dangerous concoctions, leading to people dying with much higher blood concentrations of drugs like fentanyl.

“The drugs in circulation during the pandemic now are very dangerous, and I think that's the main driver,” said Hyshka.

“We need to find ways to get people who are reliant on toxic drugs and connect them to pharmaceutical-grade alternatives and wrap-around health care.

“Many provinces are moving in this direction … but there's been no appetite to do that here.”

Hyshka said Alberta needs to adapt.

“We can't just think that adding more money to the things that we're already doing will be enough,” she said.

“We've never had a drug market this toxic, and there's no sign that it's going to go back to being less toxic.”

Kenney also announced a new online dashboard has been activated to give the public and caregivers more up-to-date information on substance abuse, with data on everything from patient counts to ambulance calls.

“An effective response begins with knowing what the problem is, and this is a huge improvement in us being able to identify what the problem is, how it's affecting people (and) where and when it's affecting people,” said the premier.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Dec. 18, 2020.