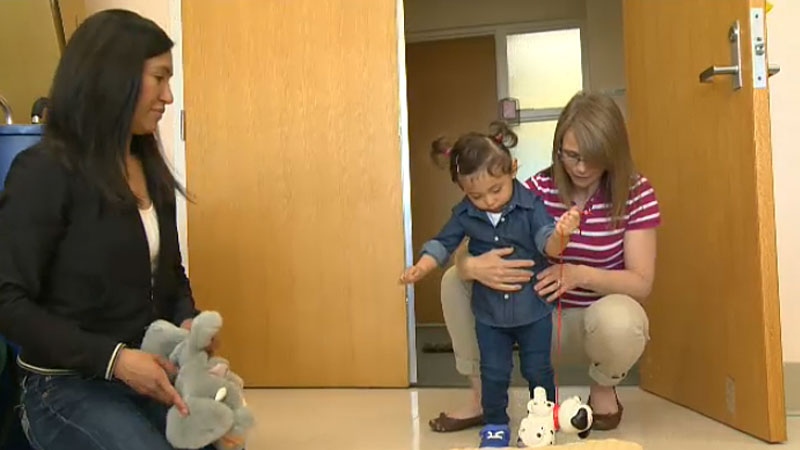

Toddler Alesandra Antipan-Delgado is slowly learning how to walk – after suffering from a stroke.

The 20-month-old young girl suffered from a stroke shortly after being born.

The stroke affected Alesandra’s entire right side.

“It was pretty scary, just heartbreaking at first,” said Rhina Delgado, Alesandra’s mother.

“The worst comes into your mind.”

One in every 1,000 babies suffer from a stroke either in utero or shortly after birth.

“I thought, how is she going to be able to walk? How is she going to be able to do things for herself? Will she able to have a normal childhood and adulthood later in life,” Rhina said.

“We were told it was quite a large stroke so she would have pretty significant physical deficits and possibly some cognitive impairment as well so it was pretty shocking and definitely a very emotional time for us.”

But thanks to the work of Edmonton researchers, young stroke patients including Alesandra are learning to walk again.

Rhina agreed to put her daughter in a pilot project – undergoing intense physical therapy including 40 one-hour sessions in just three months.

Local researchers have so far only done this physical therapy with five kids.

“So far it’s telling us that the more active they are, it appears the sooner they’ll be able to achieve walking on their own,” said physical therapist Donna Livingstone.

“We don’t have enough data to guarantee that we’re making a difference yet so that’s why we want to keep working at it to get the numbers and information to be sure but everything we’ve seen so far, the kids have done beautifully.”

'We could tell we were making a big difference'

Scientists are trying to determine what they call the “critical time period.” They want to know when the best time is to give young stroke patients treatment.

“Could we take them really early in life and actually influence the pathways that are coming from the brain which develop over the first couple of years in life,” said the University of Alberta's Jaynie Yang, lead researcher for the project.

“They came four times a week and we spent at an hour with each child at each time and after about 25 sessions we could tell we were making fairly big differences to their walking.”

Currently young patients are treated once or twice a month, usually after the age of two.

Yang believes that might be too little too late.

“My thinking is under two-years-old,” Yang said. “We’ll take children up to three-years-old and we’ll see if it makes a difference how young they are.”

The hope is that intense therapy before patients turn two might help them develop proper motor function more quickly and avoid future problems such as needing leg braces or surgeries.

“A lot of them end up with a lot of orthopedic problems in their legs because of their muscle tone and weakness on that side so we think if we can improve that situation they won’t end up having surgeries in their teens, 20s, 30s and later on,” Livingstone said.

Meanwhile Rhina says she will continue to work with her daughter to improve mobility at home.

“We’re just trying to do an hour a day of focused activity, whether it’s inside or outside, we’re really focusing on getting her to move her right leg more than her left and just to keep active for that hour,” Rhina said.

Rhina says one of the biggest outcomes of the study for Alesandra is to make sure she’s on pace with her twin brother Miguel.

“Hopefully we continue to see great progress from her and she stays on an even field with her brother. I think we just hope that she will continue to do great,” Rhina said.

“And I think she will.”

Local researchers are now launching a larger study involving 60 babies and toddlers to see how much of a difference the intense therapy is making for young patients.

With files from Carmen Leibel