EDMONTON -- A pair of local forensic experts are using facial reconstruction to identify missing people, close cold cases and bring closure to grieving families.

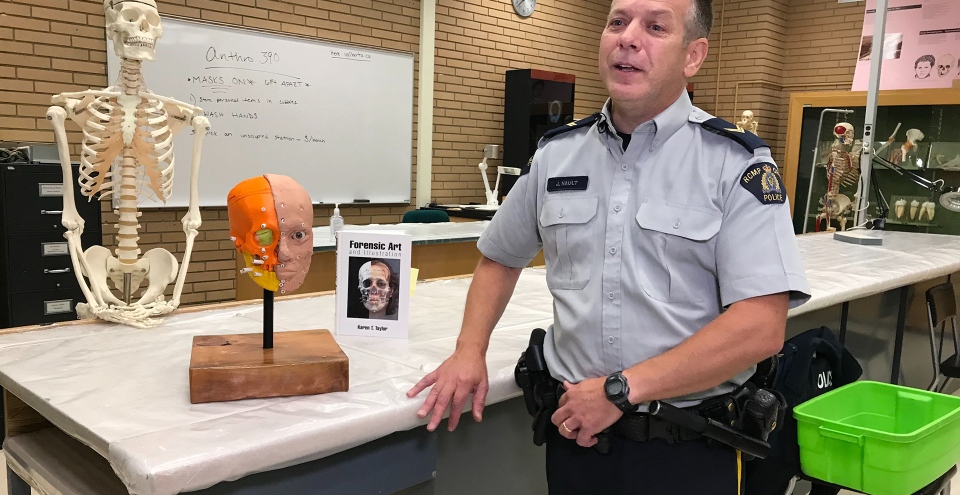

Forensic anthropologist Pam Mayne Correia and RCMP Forensic Artist Cpl. Jean Nault both have unique skills honed from years of training and scientific study.

Working out of the University of Alberta, Correia's job is to build a profile and an interpretation of a person based on human remains.

"If they are severely decomposed, if they are completely skeletonized, to bring out as much information from those skeletal remains as I can,” she explained.

From skeletal remains she is able to identify age, sex, height; but her training allows her to see more than just the basic characteristics of a person.

“We want to look at trauma, we want to look at pathology, we want to look at things that have marked that individual during life on the skeleton, so things that they've done so that we can bring forward a biography for that person.”

And when that biography has been complete, the information is passed on to Nault to exercise his special talents.

The majority of Nault’s work is making composite sketches, but five years ago he began learning how to do facial reconstructions.

Nault trained with the FBI and leading experts in forensic reconstruction. To create the reconstruction he layers an oil-based clay over top of a synthetic or actual skull to create a fleshed out approximation of what a person may have looked like.

“If there’s some trauma to the skull, then based on Pamela’s information I’ll know whether it’s recent, or whether it's old, and anything that I can use that will give me some indication of what this person look like in life, like whether he had a badly broken noses off to one side. Then we can put that onto the reconstruction, just to make it as accurate as possible,” said Nault of his process.

He says the purpose of the reconstruction is not to create an exact portrait, but to create the overall feel of the person — something that might spark a moment of recognition for someone looking at it.

“Last year, it was human remains found in Slave Lake. And we did a facial reconstruction on that, and an investigator with Calgary Police Service saw it and recognized it as somebody who is missing out of Calgary,” said Nault.

When asked if the team had a preferred type of case to work on, be it a homicide or missing person, they both had a similar answer.

As Correia put it, “Anytime we get a positive ID, that's rewarding. As soon as that person's identified and returned to their families, or their kin, that gives you the reward, and they're all about equal in that respect.”