EDMONTON -- University of Alberta researchers are studying the long-term effects of COVID-19 on the body’s most vital organs.

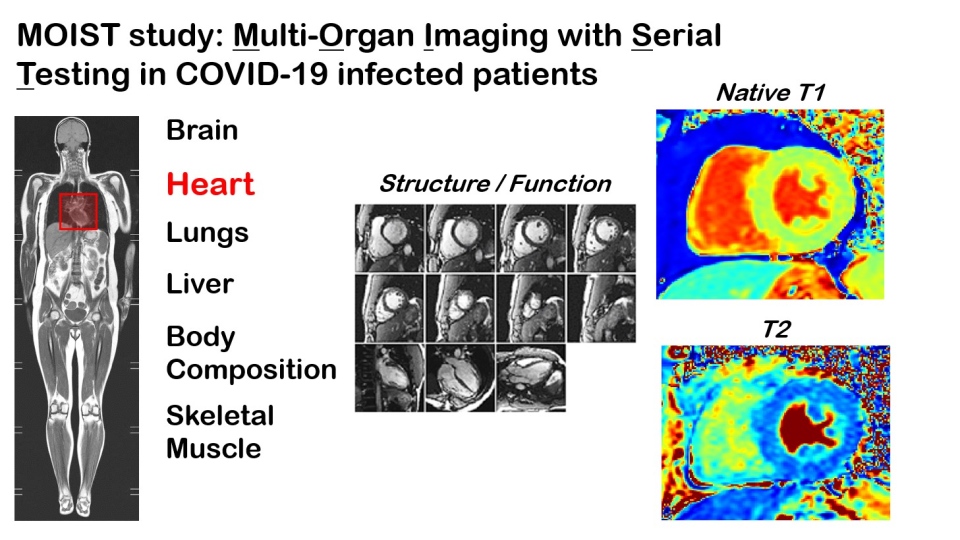

The study referred to as Multi-organ Imaging with Serial Testing (MOIST) will recruit more than 200 Albertans from the across the province who’ve had COVID-19.

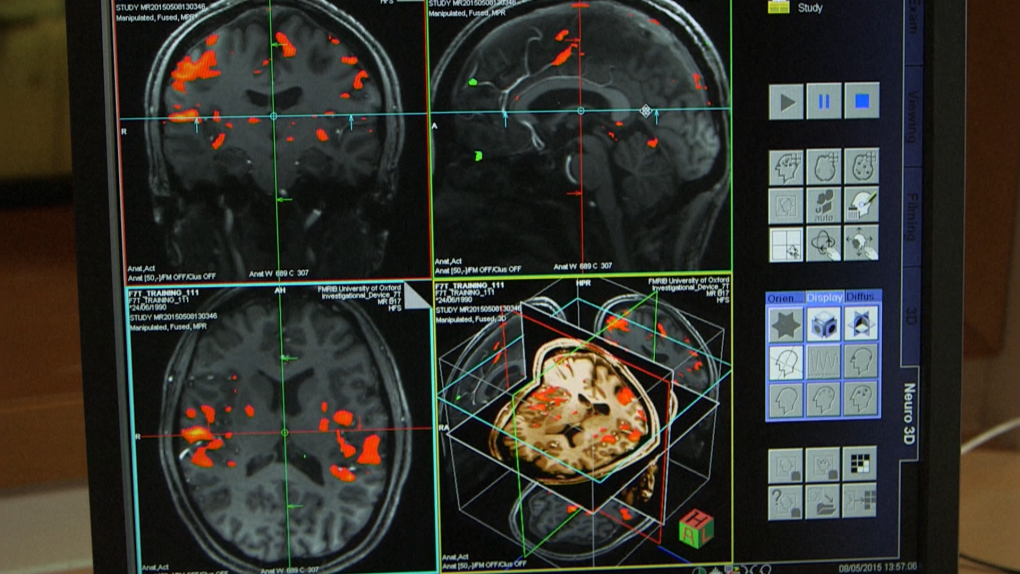

Researchers will then assess causes of inflammation in the brain heart and lungs through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Cardiologist and U of A professor Ian Paterson is leading the research team. He said the study will help give them a clearer picture of how long symptoms from COVID-19 run their course and how it affects people’s functional abilities.

“This is an illness that affects the whole body,” Paterson said.

“We’re hoping this kind of study will help identify if there are abnormalities and where they are and do they explain the symptoms people are having.”

Paterson told CTV News Edmonton each scan takes about 90 minutes and includes images of the chest, abdomen and brain. Once that step is complete, there is another 90-minute functional assessment that evaluates brain function, followed by a lung and smell test, blood work and a six-minute walk that gives researchers an idea of overall fitness.

“The most common symptoms people report after a COVID illness is fatigue and breathlessness,” he said.

“We’re looking at how well people are functioning after COVID and seeing if we can detect any signs of injury or inflammation of the organs on MRI and seeing if they correlate with their symptoms.”

According to Paterson, this has really turned into a study about Long COVID, especially after a study from the U.K. revealed 15 to 20 per cent of patients develop long-term symptoms lasting four weeks after illness.

Paterson also cited another study from Germany and the U.K. that detects 50 to 60 per cent of patients experience significant changes related to COVID-19. His team wants to see if they can detect similar findings in Alberta.

“We’re finding more people have symptoms. More than we thought would,” he said.

“To be honest, we really don’t have a great idea of how to care for these patients. We’re hoping with this type of a study it will help identify if there are abnormalities and if so where are they and do they explain the symptoms people are having.”

According to Paterson, about 100 patients have already been studied and scanned thus far, the other half are still waiting. Scanning should be complete by the summer.

The study will expand to Calgary next month. Preliminary results are expected in the fall.