U of A team repurposes culinary device to improve frostbite injury outcomes

University of Alberta researchers have created a device they believe could significantly reduce the number of frostbite cases that end in amputation.

The Frostbite Rewarming Device was inspired by data that suggested few of Alberta's growing number of frostbite injuries are being rewarmed appropriately, says Matthew Douma, a critical care adjunct professor who leads the Alberta Frostbite Care Collaborative.

There are multiple reasons for this, he knows from 16 years as an emergency department nurse, whether it be that an injured person is homeless and attends a hospital late, or that the most common way of rewarming an injury – a nurse manually supplying a series of buckets of warm water – is inefficient and imprecise.

"We didn't have a solution that was informed by the human factors or the workflow," Douma told CTV News Edmonton in a recent interview.

But effective rewarming can help preserve tissue and reduce the need for amputations and tissue grafts, so he saw an opportunity to improve both patient outcomes and treatment protocols.

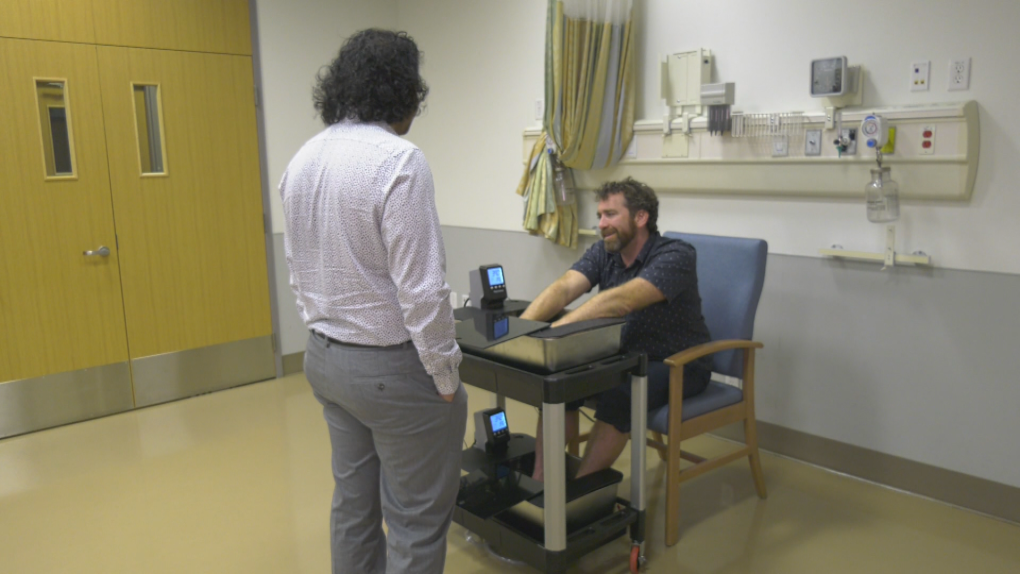

"We can't even grade the injury and decide how to further treat it until we've rewarmed the limb fully. This allows us to do it rapidly and quickly, so we'd be able to get through more patients," Douma's undergrad research assistant, Daniel Tiwana, said.

"If a frostbite is bad enough… there will be some loss. However, this could mean the difference between losing your whole finger and only half of your finger."

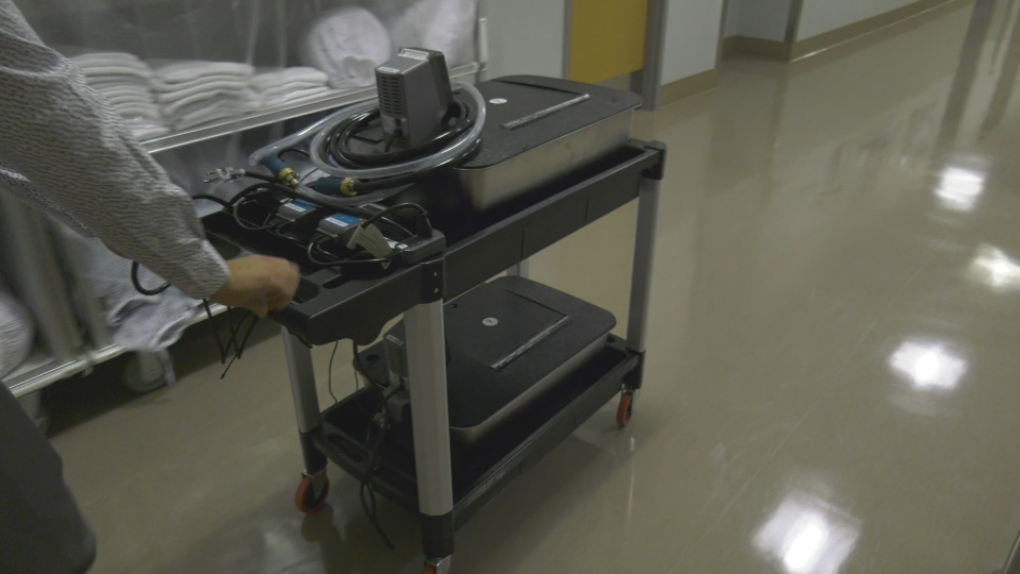

What the team came up with is effectively a mobile basin that is kept at 50 C by an immersion circulator, the same device used in sous vide cooking.

The medical-grade stainless steel basin is equipped with a hose so that it can be filled at any hospital sink, as well as a faucet so it can be emptied into a low sink or floor drain.

The circulator shuts off at 50 C and the secondary power supply shuts off at 42 C to prevent burning.

Because a quarter of frostbite cases in Alberta consist of hand and foot injuries, the device consists of a second sink at foot level so both areas can be treated simultaneously.

Matthew Douma, a critical care adjunct professor who leads the Alberta Frostbite Care Collaborative, on on Dec. 2, 2024, at the University of Alberta, soaks his hands and his feet in the Frostbite Rewarming Device to show how a frostbite patient would use it. (Matt Marshall / CTV News Edmonton)

Matthew Douma, a critical care adjunct professor who leads the Alberta Frostbite Care Collaborative, on on Dec. 2, 2024, at the University of Alberta, soaks his hands and his feet in the Frostbite Rewarming Device to show how a frostbite patient would use it. (Matt Marshall / CTV News Edmonton)

The two basins are housed in a wheeled cart that can be moved anywhere needed, so long as there is a nearby electrical outlet. If an outlet is not available, the device can be powered for one hour by battery.

"With a device like this, that health-care professional can fill it, plug it in, get the patient sorted and settled, and actually go about maybe providing pain medication, assessing and treating other patients," Douma said.

"So really, it's almost like a force multiplier. It does a better job of rewarming, but also frees up health-care staff to do other roles."

The product is only a prototype at the moment and has not been used to treat humans. However, in trials on frozen animal limbs, the device has appeared promising, Douma's team says, having achieved target temperatures faster than traditional methods and produced lower outcome variability.

Matthew Douma, a critical care adjunct professor who leads the Alberta Frostbite Care Collaborative, wheels the team's invention, the Frostbite Rewarming Device, down an University of Alberta hall on Dec. 2, 2024. (Matt Marshall / CTV News Edmonton)

Matthew Douma, a critical care adjunct professor who leads the Alberta Frostbite Care Collaborative, wheels the team's invention, the Frostbite Rewarming Device, down an University of Alberta hall on Dec. 2, 2024. (Matt Marshall / CTV News Edmonton)

He hopes to get the device not only approved for use in hospitals, but also shelters and urgent-care facilities, which frequently see frostbite injuries.

"As soon as frostbite is discovered in that emergency shelter, if you can start this therapy, it could help prevent those amputations and the requirement for skin grafting and loss of function," Douma said. "They should still call 911… but if you can rewarm people at the site and then keep it warm, we believe the outcomes will actually be better."

With files from CTV News Edmonton's Connor Hogg

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Trump making 'joke' about Canada becoming 51st state is 'reassuring': Ambassador Hillman

Canada’s ambassador to the U.S. insists it’s a good sign U.S. president-elect Donald Trump feels 'comfortable' joking with Canadian officials, including Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Mexico president says Canada has a 'very serious' fentanyl problem

Foreign Affairs Minister Mélanie Joly is not escalating a war of words with Mexico, after the Mexican president criticized Canada's culture and its framing of border issues.

Quebec doctors who refuse to stay in public system for 5 years face $200K fine per day

Quebec's health minister has tabled a bill that would force new doctors trained in the province to spend the first five years of their careers working in Quebec's public health network.

Freeland says it was 'right choice' for her not to attend Mar-a-Lago dinner with Trump

Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland says it was 'the right choice' for her not to attend the surprise dinner with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at Mar-a-Lago with U.S. president-elect Donald Trump on Friday night.

'Sleeping with the enemy': Mistrial in B.C. sex assault case over Crown dating paralegal

The B.C. Supreme Court has ordered a new trial for a man convicted of sexual assault after he learned his defence lawyer's paralegal was dating the Crown prosecutor during his trial.

Bad blood? Taylor Swift ticket dispute settled by B.C. tribunal

A B.C. woman and her daughter will be attending one of Taylor Swift's Eras Tour shows in Vancouver – but only after a tribunal intervened and settled a dispute among friends over tickets.

Eminem's mother Debbie Nelson, whose rocky relationship fuelled the rapper's lyrics, dies at age 69

Debbie Nelson, the mother of rapper Eminem whose rocky relationship with her son was known widely through his hit song lyrics, has died. She was 69.

NDP won't support Conservative non-confidence motion that quotes Singh

NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh says he won't play Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre's games by voting to bring down the government on an upcoming non-confidence motion.

Canadians warned to use caution in South Korea after martial law declared then lifted

Global Affairs Canada is warning Canadians in South Korea to avoid demonstrations and exercise caution after the country's president imposed an hours-long period of martial law.