EDMONTON -- Before Najwa Karamujic drives home, she sprays down her entire body with aerosol disinfectant.

She can't have any contact with her family once she's home. First, she goes to the laundry room and changes, making sure her old clothes are turned inside-out before going into the washing machine.

She then disinfects every hard surface she touched on her way to the laundry room. Only then can she have some form of normalcy, including spending time with her 80-year-old mother.

Karamujic is the pandemic response coordinator for the Chipewyan Prairie First Nation (CPFN). She tends to those who are quarantined. She also helps community leaders prepare for potential future waves of COVID-19.

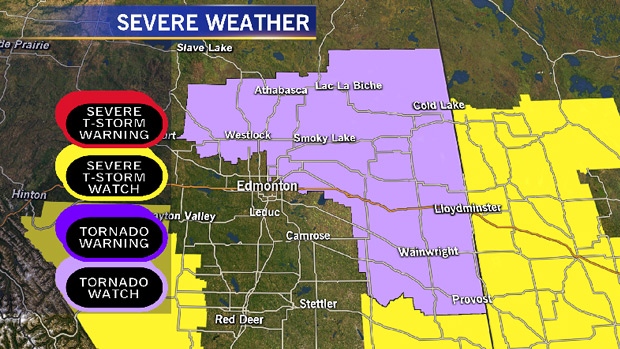

The First Nation, which is adjacent to Janvier, has been one of the hardest hit communities in Wood Buffalo. As of Sept. 30, there are no active cases in the community and no one has died.

Warmer weather and a May funeral in La Loche, Sask. led to 44 COVID-19 cases this past summer, or 65 per cent of all cases in the region's rural communities.

Anyone unable to quarantine at home was moved to an isolation facility in Fort McMurray managed by the Athabasca Tribal Council.

Sometimes patients need groceries, sometimes they need a Tylenol, sometimes they need toothpaste and sometimes they just need to talk to someone. Karamujic was hired in June to provide all of these needs.

“When you're dealing with a frontline crisis, it's easy to forget that these people have lives outside of being isolated in a very sterile environment,” she said.

Karamujic has 10 years of experience working for the Nation. While she is not a member herself, she brings familiarity and friendliness to her work.

Being that familiar face in a sterile isolation unit makes all the difference for people feeling lonely or anxious. Some patients would be isolating for awhile and would get stir crazy in their rooms.

“We just wanted someone who kind of understood what these folks were going through and had a sensitivity to what our members in Janvier expect in terms of contact,” said Matthew Michetti, executive assistant to Chief Vern Janvier

One 20-year-old COVID-19 patient had not been home in 21 days. He spent a week in an ICU and spent two weeks recovering at Fort McMurray's quarantine site.

Karamujic was the one to tell him he would be going home the next day.

“He was very stoic and didn't show a lot emotion,” she said. “When he closed the door, you could hear him just screaming and calling his friends and family to tell them he was coming home.”

Other days have been harder. There are times when Karamujic fears for her safety, especially around active cases.

When checking on an older man with COVID-19, Karamujic had to enter his room to speak with him. He was in bed and hooked up to an oxygen unit. She was wearing a mask, face shield, gown and gloves. Her duties can keep her on call 24/7.

“There was a time where I put in 121 hours in very short time,” she said. “You're tired and you become a bit of hypochondriac.”

Mentally separating the stress of her job from her home life is necessary for Karamujic.

“At the end of the day it's a job and you have to make sure you do your job well,” she said. “But life doesn't stop because you're in a facility with positive COVID cases.”

After nearly four months on the job, Karamujic said she and the First Nation have learned some hard lessons about managing COVID-19.

The economic impacts of COVID-19 lockdowns have been particularly hard on people. The community also restricted access to outsiders. The consequences of the 1918 Spanish Flu, which killed all but 12 families in the Janvier area, meant community leaders wanted to take no chances.

Karamujic said the First Nation is studying the past six months to prepare for future waves.

CPFN is working with Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) and the First Nations Inuit Health Branch to bring isolation units onto the reserve. This will keep any potential patients living with extended families from having to quarantine in Fort McMurray.

One of the main things Karamujic said she has learned from her work is patience. Everyone is learning as they go.

“As our community heals from this journey, we're always looking at what we're doing and how we can do it better,” she said.