The Auditor General of Alberta has released a report on the Ministry of Human Services, the department in charge of providing child and family services – identifying inadequacies in the department and how services are provided.

The report said the provincial government could improve how child and family services are provided to indigenous children, especially when it comes to keeping families together and seeking permanent homes for children in permanent care. The report states outcomes for indigenous children aren’t as favourable.

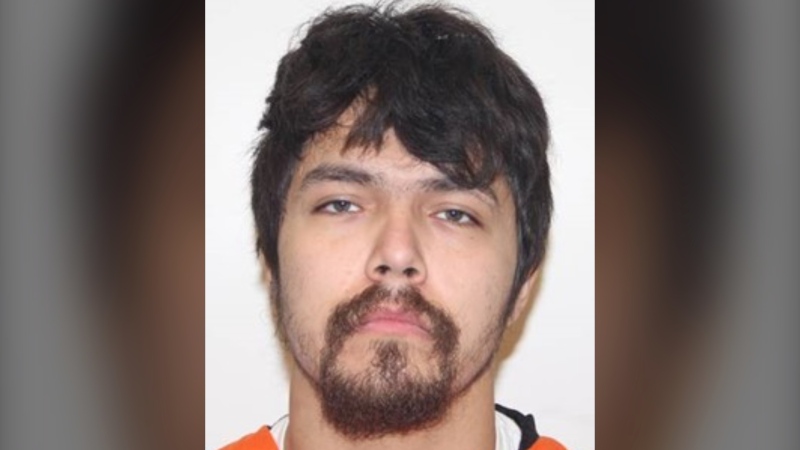

Shaye Trudel has faced a struggle with her identity – the 19-year-old is Metis.

“People judge you because you look a certain way,” Trudel said.

“When I tell people I’m Metis, I get a lot of stuff like ‘Oh well, you’re just a half breed’,” Trudel continued.

Four years ago, Trudel sought help at a local youth centre.

“I don’t know where I’d be without having the support that I had from them, because it was just a really tough time in my life,” Trudel said.

And she’s not alone – the centre has helped many indigenous youth.

“They’re experiencing things like suicide, addictions, homelessness, health issues, at a much higher rate than non-aboriginal youth,” Leeanne Ireland at the Urban Society for Aboriginal Youth said.

Ireland said the sources for the pain these youth face are deeply rooted.

“The impact of residential schools, and then even later the sixties scoop, and even now some youth’s involvement in the child welfare system, they’ve all created a system of trauma,” Ireland said.

According to the Auditor General report, the province’s Human Services Ministry can make improvements in three areas: the report suggests the government should enhance early supports for indigenous children and families, and should make sure care plans are individualized and meet the same standards as those for non-indigenous children.

“A blanket strategy for all children will fail to close the gap between indigenous and non-indigenous childrens’ experiences of support,” Auditor General Merwan Saher said.

Plus, the report said provincial staff should be better educated on the history and culture of indigenous peoples.

Another independent report by the Child and Youth Advocate also released Tuesday states that approximately 70 percent of the children in Alberta’s child welfare system are aboriginal.

Human Services Minister Irfan Sabir released a statement in response to the reports, accepting the recommendations outlined, and saying the “over-representation of Indigenous children and youth in care is an issue that we must address”.

Indigenous Relations Minister Richard Feehan also responded, saying it was clear changes needed to be made:

“Front line workers strive to help at-risk children in Indigenous communities, but it’s clear the status quo isn’t working. We need to think differently and have real, community-driven conversations about how to close the gap.”

However, Ermineskin Cree Nation Chief Randy Ermineskin pointed to some issues he says will take longer to resolve.

“Juristdictional Boundaries continue to create challenges and barriers that prevent access to services for First Nations children, and in addressing the best interests of the child,” Ermineskin said.

Meanwhile, Trudel is worried young women like her who don’t have access to the same supports she did may fall through the cracks.

“Without [that support] I don’t think I’d be where I am now,” Trudel said.

Minister Feehan said he was planning to start meeting with communities as early as this summer – he told CTV News he’s seeking feedback on what individual communities need before making any changes.

With files from Shanelle Kaul and Nicole Weisberg